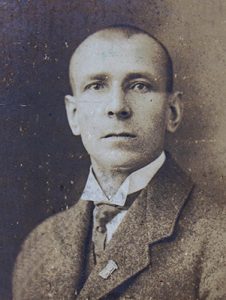

Jan Šrubař

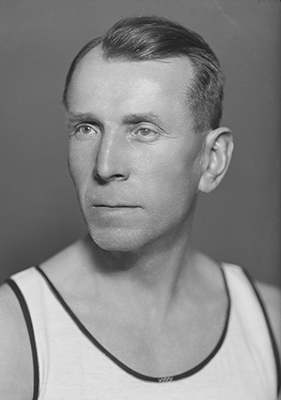

Father of seven children, soldier, member of the Sokol Union, patriot, sportsman in body and spirit, promoter of skiing, WWII resistance fighter, and hero who was tortured to death by the Nazis. A man with a capital M. A man who died for freedom. A man who would not budge till the bitter end.

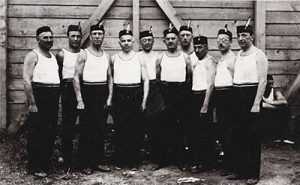

Jan Šrubař was born on 17 December 1885 in Frenštát pod Radhoštěm. He trained as a machinist and went to Pardubice and Dresden for experience. After his return, he worked as a machinist until World War I. In 1911, he married Marie Rečková, who became his lifelong support and, especially in later difficult times, bravely shared their common ideals. Already during his apprenticeship, he became a member of the patriotic Sokol Union and his love of sport accompanied him throughout his life.

Jan Šrubař was born on 17 December 1885 in Frenštát pod Radhoštěm. He trained as a machinist and went to Pardubice and Dresden for experience. After his return, he worked as a machinist until World War I. In 1911, he married Marie Rečková, who became his lifelong support and, especially in later difficult times, bravely shared their common ideals. Already during his apprenticeship, he became a member of the patriotic Sokol Union and his love of sport accompanied him throughout his life.

At the end of the first decade of the 20th century, he discovered the magic of skiing – a pastime available to few at the time – and it became a lifelong devotion that defined his sports career, as well as the professional one.

Cinema and theatre were also within the scope of Jan Šrubař´s interests. As early as 1912, he founded a cinema and theatre hall in Frenštát under the auspices of the Sokol Union and he himself helped with theatre performances and film screenings.

But then, World War I came.

He had to enlist and served in the fortress artillery. However, as a result of burns suffered during gunpowder explosion, he was discharged from the army in 1917 and joined a factory in Kopřivnice. Upon his return, he sensed the chance for the establishment of an independent Czechoslovak state and multiplied his patriotic efforts.

In 1918, although the Frenštát Sokol Union was banned in 1915, he organized a May Day Sokol trip to Horečky, and in the autumn of the same year, he became a member of the local committee ensuring the smoothest possible transition from the monarchy to the new Czechoslovak Republic.

However, Sokol activities, theatre, and skiing remained his priorities. Eventually, he quit his job and started making ski bindings in his own workshop. These he assembled with skis made by a local carpenter to improve the accessibility of skiing for others. In 1924, he opened a ski rental shop in Frenštát so that everyone could try the sport he loved and initiated the construction of a ski jumping ramp in Pustevny. He also organized ski races, the costs of which he often subsidized from his own funds.

However, as a result of the economic crisis during the 1930s, which led to contracts for goods he already produced being cancelled, his house and workshop were foreclosed and Jan Šrubař moved to Valašské Meziříčí. There, together with other enthusiasts, he continued to organize competitions and acted as a coach in the local sports ski club. He also trained his sons, who were successful at the national level; the eldest of them even represented Czechoslovakia and took 20th place at the World Championships. He was also an active participant himself. At the age of 53, Jan Šrubař became a sovereign winner in the category of older competitors at the Winter Games of the Czechoslovak Sokol Community in the High Tatras.

which led to contracts for goods he already produced being cancelled, his house and workshop were foreclosed and Jan Šrubař moved to Valašské Meziříčí. There, together with other enthusiasts, he continued to organize competitions and acted as a coach in the local sports ski club. He also trained his sons, who were successful at the national level; the eldest of them even represented Czechoslovakia and took 20th place at the World Championships. He was also an active participant himself. At the age of 53, Jan Šrubař became a sovereign winner in the category of older competitors at the Winter Games of the Czechoslovak Sokol Community in the High Tatras.

He enjoyed great respect within the Sokol Union, as evidenced by the fact that he became the chief of the entire František Palacký Sokol County of Wallachia, the second oldest in Moravia.

By then, however, the clouds of World War II were gathering over Europe.

The patriot Jan Šrubař could not accept the occupation and immediately joined the resistance. At first, he established cooperation with the group “Obrana národa” (Defence of the Nation); later, based on a bad experience with the carelessness of some members, he decided to create an organisation himself using reliable people he knew from the Sokol environment. In particular, he was helping suggle people over the mountains to Slovakia, organizing transports of people, arms and ammnition.

The patriot Jan Šrubař could not accept the occupation and immediately joined the resistance. At first, he established cooperation with the group “Obrana národa” (Defence of the Nation); later, based on a bad experience with the carelessness of some members, he decided to create an organisation himself using reliable people he knew from the Sokol environment. In particular, he was helping suggle people over the mountains to Slovakia, organizing transports of people, arms and ammnition.

However, as happened to so many other resistance fighters, he was denounced to the Gestapo. The Gestapo raided the Šrubař´s home for the first time in February 1940, when Jan Šrubař was lying with a broken leg. The Gestapo limited their raid to the search of the house but came back several times over the next months; still, they found no weapons nor other incriminating materials.

In November 1940, however, Jan Šrubař was arrested and taken to Ostrava. Despite three months of torture, when he spent the entire time in shackles and underwent terrible beatings and abuse at any hour of the day and night, he confessed nothing and betrayed none of his associates. Even his tormentors themselves eventually felt a grudging respect for him. When Šrubař´s sons Jan and Václav were arrested in April 1941, the interrogating Gestapo officer told one of them:

Your father can take a beating! And you don´t have to be ashamed of him, he had it all well organized!

At that time, however, Jan Šrubař Sr. was already in a prison/forced labor camp in Wohlau (today Wólow, Poland, near Wrocław). In May, both of his arrested sons were sent to the same prison, and as much as he had to agonize over their fate, it at least allowed them to support each other with secretly passed notes. In October, he was transferred for some time to Wrocław for judicial investigations, together with other members of the group “Obrana národa”, and he also spent some time in the Alt-Moabit prison in Berlin. The trial itself, during which he was sentenced to death, took place in November 1942, again in Wrocław.

After his sentencing, his conditions got even worse: he was transferred to solitary confinement in the “dungeon of death” where frequent torture was added to the constant shackling and inspections every five minutes. Yet, he refused to give his tormentors the last satisfaction.

“They won´t get me under the axe,” he said long before his sentencing.

And they didn´t.

As the day of his execution approached, the inflamed wounds from the torture led to sepsis from which he died on February 7, 1943.

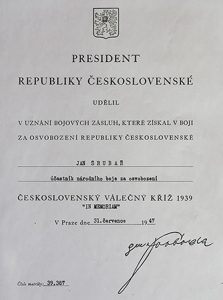

Thus died a man who loved the Beskydy Mountains, sports, and his country. A man who, for the sake of his and others' freedom, endured things that are unthinkable for us today. A man who was awarded the Czechoslovak War Cross in memoriam in 1947.

A man whose legacy should be remembered. And that is why the Jan Šrubař Memorial is here.

We cooperate with the Society for Preservation of Resistance Traditions![]()

and